From Cornwall to the world

PART 2: Pasties

Dear Naomi,

Thanks for your letter and this week’s inspiration. Pasties are close to my heart; my Uncle lived in Cornwall and married a Cornishwoman from a very large family, with many generations of excellent bakers. Just for the record, they pronounced it in the same way that you did – phonetically passtie rather than parstie. Perhaps the ‘ar’ variation is a pronunciation more common in Australia than England, but no doubt someone will prove me wrong.

Many cultures have the tradition of small pastries, often hand-held; I’m thinking of Spanish empanadas, Indian samosas and Italian calzone. It seems the pasty we are most familiar with has its origins in the Cornwall. But even this seemingly innocuous statement is fraught with the risk of being howled down by all manner of cooks, food writers and historians: the most recent theory I came across is that the pasty in fact originated in Devon and was appropriated by the Cornish; as always, each of these theories is staunchly defended with unwavering certainty; the world of food is awash with such arguments! There is an official encyclopedia of the Cornish pasty, a pasty association, and countless methods of making this substantial and nourishing meal. Some opinions state that if a pasty contains potato it is known as a ‘tiddy oggy’, without potato it’s a ‘hoggan’.

Yet another variation is a pasty with a savoury filling at one end, and sweet at the other. In other parts of the UK, there is a regional version of this sweet/savoury combination known as a Bedfordshire Clanger, which uses a stiff lard or suet pastry.

Whatever theory you choose to favour, it’s certain that the pasty has been made for centuries, and may have had links back to when dough was used as a serving platter, rather than an edible component of the meal. Initially it was a food for the wealthy; fillings such as venison, beef, lamb and seafood reflect this wealth. It wasn’t until the 17th and 18th centuries as Cornwall became the mining centre of the world, that the pasty became the food associated with the miners. The depths of the mines and the difficulties of access meant that returning to the surface for a midday meal was not practical, and so the pasty was designed to provide vital sustenance in a portable form. As the tin mining industry began to flag in the UK, Cornish miners left to seek their fortune in such far-flung lands as Australia and the Americas, taking Cornish pasties with them, where they continue to be extremely popular. The Cornish pasty industry is estimated to contribute 300 million pounds to the Cornish economy annually, with over 120 million pieces sold.

As though the dank darkness and ever-present danger of such work were not enough, arsenic is often present in tin mines; there is a theory that the thick, crimped crust was used as a handle, allowing the filling to be eaten without contamination from blackened hands.

Have you ever been down a mine? I once had the opportunity to go down a gold mine in Bendigo; it was then that I absolutely identified as claustrophobic. The moment we stepped out of the cage lift to be told just how far underground we actually were (61 metres, which is nothing compared to the 1,000 metres of some mines in Cornwall) my heart began to race, my breathing became shallow and rapid and I just couldn’t wait to get out! I can’t, therefore, tell you much about the actual workings of the mine, but I can tell you that I have enormous admiration for those generations of adults, children and ponies that spent their entire working lives underground in such terrifying and dangerous circumstances!

The classic recipe for a pasty was beef, potato, onion and swede/turnip; as meat is an expensive ingredient, the pastie was often vegetable-heavy. As always, there are endless arguments about what should and shouldn’t appear in the mix; carrots, popular today, were once considered the sign of an inferior pasty.

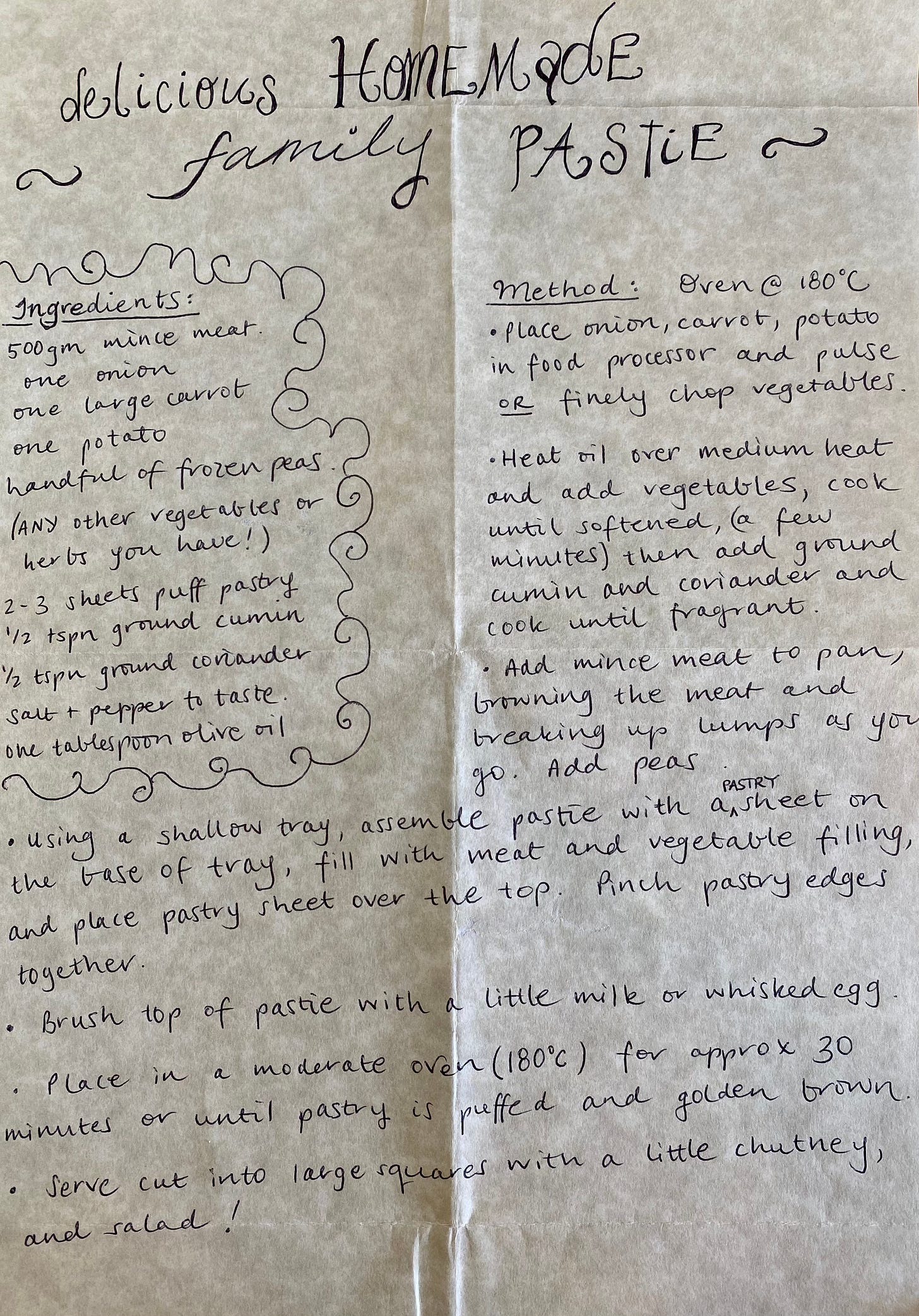

Similarly, this is not a dish for light, flaky pastry, versions of shortcrust using lard and suet were common, as this makes a robust, sturdy casing. Jo’s recipe calls for puff pastry, but as I was unable to buy puff (supply issues) and am not planning to make my own, I have chosen to use high quality prepared sour cream pastry, hand-made in Australia.

Despite all the many variations, the one thing all methods had in common was that the ingredients were encased in their raw state and cooked through along with the pastry. This dictated that the filling should be reasonably finely diced and all pieces of much the same size. Again, Jo’s recipe does not adopt this method, but cooks the filling ingredients before making the pasties. As I have always baked my pasties with an uncooked filling, that is what I’ve done here (sorry Jo).

Whatever you call it, and however you choose to make it, the pasty is always a comforting, reassuring thing to bake; and next time you do, Jo’s Grandma will live on in your kitchen too…

All the best…